Thomas Morton: Early Colonial New England's "Lord of Misrule"

A glimpse into the life of Thomas Morton: the English attorney who fell in love with New England in the 1620s. The Pilgrims at Plymouth hated him so much, they exiled him from Massachusetts 3 times.

The superficial story of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, Massachusetts—the Thanksgiving Holiday mythos—is known to all Americans in one form or another. In their written histories, colonial founders depicted the English settlers as having pious and virtuous goals. Contemporary, critical counter-narratives defy this, by claiming that the English were nothing more than violent oppressors bent on destroying the remnants of native Algonquian culture.

One of the Pilgrims’ neighbors, Thomas Morton, is a more obscure figure in New England’s history, presenting more complexity to the picture. Rather than outright conquest, Morton imagined a future of cooperation between the English and Algonquians. He criticized the Pilgrims as being less Christian in their virtues than the native people. He fell in love with the abundant nature of the pristine country, and let his imagination run wild with possibilities.

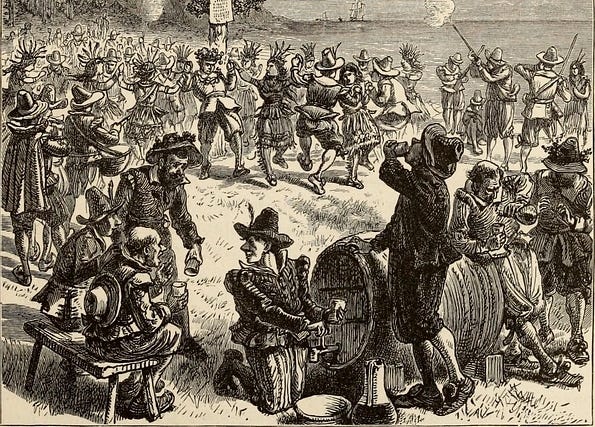

He was also known for throwing wild parties at his outpost settlement at Merrymount. Most traditional historians have focused on the vices: the drunken maypole dancing, cavorting with Indians, alleged attempts to reestablish pagan rites. An early governor of the colony at Plymouth, William Bradford, worried about the survival of his fledgling community, declared that the “Lord of Misrule” Morton had founded a “school of Atheism” at Merrymount, where they

…set up a may-pole… drinking and dancing about it many days together, inviting the Indian women for their consorts, dancing and frisking together (like so many fairies, or furies rather) and worse practices.

Counter to this, over the past century writers have attempted to paint Morton as an anti-establishment folk hero, running with the premise of Bradford’s narrative but coming to a different conclusion. In Philip Roth’s The Dying Animal, the lecherous, senior literature professor, David Kepesh, declares that it should have been Morton whose face appeared on Mt Rushmore, that in opposition to the Pilgrim’s “virtuous utopia” was a “utopia of candor” at Morton’s Merrymount, likely referring to Morton’s rebellion of authenticity against the Pilgrims. While figures like Bradford made a devil out of Morton, Roth’s character uses Morton to justify his 60s free love escapades. Rather than denying the devil in Morton, Kepesh implies Morton was a devil, and here’s why that was a good thing!

Rather than “picking sides” in examining Morton’s life, we can continue the tradition of seeing how he was a narrative-smashing figure, but avoid merely reacting to the historical narrative premise established by the Pilgrims.

===

England had survived a potential invasion by Spain in 1588 with the defeat of the Armada in 1588. A growing sense of nationalism fostered a strong desire for England to assert itself on the global stage. An increasing number of people were discovering North America in books, through the captivating narratives written by explorers. Sailors brought back physical curiosities from across the ocean, including kidnapped natives who were paraded around on grotesque tours to excite gawking crowds.

Unlike the Spanish, the English in the early 17th century struggled to colonize the New World. Their many failed attempts include the famed “Lost Colony of Roanoke”, a few attempts in Virginia, and a colony in modern-day Maine. John Smith’s colony at Jamestown survived, but the situation there remained rocky for years.

In 1614, John Smith sailed to the region north of Virginia. He mapped out the shoreline and gave it a new name: New England. His report of the region attracted the attention of the religious dissenters, later known as the Pilgrims, who came to Massachusetts in 1620. The colony at Plymouth was a relative success, and inspired men of ambition to seek fortune in New England. Among them was the soldier and politician Ferdinando Gorges, who hired Thomas Morton to join an expedition to the New World in 1622.

Earlier that year, Morton and his son-in-law George had been engaged in ferocious legal battles that ended up bringing them to the highest courts in England. His son-in-law was known to be difficult, uncharitable even to his own siblings, and it’s likely Morton grew tired of the disputes. It’s unknown to history what Alice Miller thought about her husband’s departure; she was the wealthy widow who Morton married, after he served as her legal counsel. We don’t know Morton’s thoughts on the separation either, so we can only speculate on the matter. Without a doubt, New England would have been an attractive option for a 17th-century Englishman of means looking to escape a mid-life crisis.

Morton’s first visit in the winter of 1622/1623 lasted only a few months. He returned in 1624 as part of another expedition. They founded a settlement and named it Mount Wollaston, after Captain Richard Wollaston, the leader of the expedition. The captain, however, left shortly thereafter, taking most of his crew to Virginia. Historical accounts vary, but some claim the harsh New England winter spurred Wollaston to travel south.

Morton took charge of the colony, by then a group of no more than a dozen men. His newfound home was near a hilltop overlooking a bay. He renamed the place “Ma-Re Mount” (later simplified as Merrymount). At a festive ceremony, with the company of native Algonquians, they celebrated with dancing, drinking, and carousing for many days. In the center of the festivities stood an 80 foot tall maypole crowned with deer antlers at the top.

Gossip spread quickly in the colonies, so it probably didn’t take long for Morton’s neighbors to hear about the raucous festivities. The Pilgrims would have frowned upon such excesses, but they were more concerned about Morton’s trade policies. He sold firearms to the natives, and also alcohol. Morton denied the latter, claiming he only gave liquor to the tribal leaders as gifts (and he couldn’t help it if the chiefs passed along the gift to others).

Plymouth colonial authorities sent warnings to Morton to stop trading, but he refused. Captain Miles Standish showed up armed to take Morton. Morton and his gang had barricaded themselves indoors, but decided not to engage in violence.

After standing trial in Plymouth, the court banished Morton from Massachusetts. Morton was taken to the Isles of Shoals, marooned on a barren island where the Pilgrim leaders hoped he would starve to death. Sympathetic Algonquians brought him supplies, though they didn’t dare bring him to the mainland, for fear of upsetting the Pilgrims. The Pilgrims meanwhile chopped down his maypole at Merrymount, and renamed his settlement Mount Dagon, after an ancient Sumerian deity, as if to curse the place for all time.

After a month stuck on the island, Morton caught a ship that took him back to England. But he was not discouraged, and made a speedy return to Plymouth in 1629, this time to work as a scribe for a man named Isaac Allerton. Morton didn’t stay at this post for very long, returning soon to his old house at Merrymount. In the meantime, the Pilgrim authorities were keen on getting rid of Morton again.

Historical records aren’t exactly clear what Morton did to provoke being arrested, other than perhaps causing general annoyance or not complying with formal legal requests or contracts. He wasn’t trading alcohol or guns anymore, at least on a large scale. There were no more maypole parties for that matter, either. It seemed this time Morton simply wanted to live out a new life and not bother anybody.

But the Pilgrims, so that the “habitation of the wicked” be destroyed once and for all, made a rather dramatic statement when a posse came to seize Morton’s property at Merrymount and burn the house to the ground. This was done in the sight of a company of Algonquians, who according to Morton, ridiculed the Pilgrims for burning perfectly good shelter with the oncoming of winter. Morton was then sent back to England in 1631, in the hopes that he would be imprisoned.

This was a fateful move. When Morton returned to England, he had grounds for legal grievances against the Plymouth colonists, since they had seized his property by force. Had the Pilgrims left Morton alone, he might have just wandered off further into the wilderness.

Even more important to us here in the present day: had the Pilgrims not exiled Morton to England, we likely would not have the book written by him, New English Canaan, which presented events at Merrymount from his perspective.

Back in London, Morton took action with his allies there, including his friend Fernando Gorges. Gorges was still interested in founding a colony in Massachusetts and thought that the Pilgrims’ colonial charter was on shaky legal ground. If they could convince the King of England that the Pilgrims’ charter was invalid, then they could uproot the obnoxious “separatists” from New England for good.

Morton’s New English Canaan was in part a collection of legal briefs and testimony to his cause, as well as notes on the native peoples of the region and resources the country would provide for a colony. He emphasized the foolishness of the Pilgrim community and their separatist nature, indeed their own misrule. King Charles would have been growing more concerned about agitations by religious separatists. New English Canaan has a clear royalist bent to it, which must have been by design. The Monarchy looked with favor upon the efforts of Gorges and Morton, and made a formal request for Massachusetts to send its charter back its charter to London. Meanwhile, Morton’s book was published in Amsterdam in 1637, due to apparent disruptions by agents from the New England colonies in London. It is miraculous that the book even survived, since its publication was suppressed and it was banned in New England.

Ultimately, Morton did not get the legal outcome he desired. Massachusetts did not send its charter back, and soon, England exploded into civil war and the King had more pressing matters close at home to deal with. Gorges, meanwhile, received a patent for a colony in Maine, where his historical legacy in America is most familiar today.

When Morton finally returned to Massachusetts again in 1643, about twelve years since his last banishment, the authorities jailed him immediately on suspicions of being an agent of King Charles. The charge wasn’t completely unfounded, given the war between royalist and parliamentary (Puritan) forces.

One can envision Morton, wistfully considering retirement options and longing to be back in his beloved New England, but he just about picked the worst place and time to go back. The Puritans firmly ruled Massachusetts Bay in 1643. They weren’t separatists like the Pilgrims, but wanted to transform the Church of England to their revolutionary vision. Massachusetts had thus become a hotbed of anti-royalist sentiments. The policy of the Massachusetts Bay Colony regarding the natives turned to one of slaughter: the Pequot War of 1637 had been brutal. Morton's vision of cooperation and knowledge sharing between the colonists and Algonquians was shattered beyond repair.

Morton, languishing in jail, was in poor health because of his age. The authorities granted him clemency. He spent the rest of his days in exile once again, in Maine, and died at Acamenticus in either 1646 or 1647.

===

The story from Morton’s perspective might have been lost entirely, were it not for John Quincy Adams, a future President of the United States. While serving a diplomatic role with Prussia in the early 1800s, Adams happened upon a copy of New English Canaan in Berlin. Incidentally, his father, John Adams, was familiar with Morton, since his colony at Merrymount had been on what was then family property.

Copies of the book began to be reprinted in the 19th century, and interest in Morton grew among newer historians and writers, along with a critical reassessment of the early colonial founders. The author Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote a fictional account of Merrymount, a work that wasn’t faithful historical fiction, but an allegorical “romance” inspired by the events there. Still, it got people thinking about the myths of New England’s founding.

With Hawthorne's story and the reprinting of New English Canaan, Thomas Morton was increasingly viewed as a radical folk hero, a social reformer, or a visionary of utopian ideals. This perception persisted throughout the 20th century. Many indeed characterized him as being a “pagan,” or his settlement at Merrymount as being an experimental renewal of Greco-Roman paganism in America. The irony of this is that supporters of Morton were using an epithet that the Pilgrims used against him.

We can’t know for sure what Morton’s exact beliefs were. At least on paper, Morton was an Anglican Christian, colored by Elizabethan culture and education, and had a fondness for classical mythology. What we do know however, is that he was far less interested in hard-line religiosity and theocratic state building than his adversaries in Massachusetts, though in his writing he makes just as many literary comparisons to the Bible as he does classical Greek and Roman mythology. Indeed, though Morton acknowledged the dignity of the Algonquians, like many of his contemporaries, he wished to work for the speedy conversion of the natives to the Church of England.

Despite some of his raucous behavior, Morton would have been a traditionalist in 1620s New England, in the sense that he was interested in upholding traditions of England, its Church, and the deeper mythology of its civilization. Too many researchers can get fixated on the symbol of the maypole, and on pagan rites, though in reality setting up a maypole was quite normal practice outside of less puritanical communities in England, and had been a common amusement since Medieval times.

Nowadays, religious fundamentalism strikes us as backwards or reactionary. However, it’s important to remember that despite their religious fundamentalism, separatists like the Pilgrims and Puritans were forward-thinking progressives, even revolutionaries. Along with eliminating all traditional holidays, including Easter and Christmas, some Puritans considered renaming the days of the week and months of the year to erase connections to Roman paganism altogether. The Jacobins’ effort to implement the French Republican Calendar come to mind, or the Chinese Red Guards’ desecration of the Ming tombs to exorcise the Four Olds.

Perhaps to best honor Morton, in true Elizabethan fashion, we might consider wisdom out of Shakepeare’s Hamlet: if we encounter a ghost, as the scholar Horatio, we might speak to it. And not speak too much for this ghost, but listen. Luckily for us, we have Morton’s testimony in New English Canaan and can hear from the man himself.

In the next article, we’ll take a deeper dive into New English Canaan, highlighting some of the more fascinating and entertaining observations made by Morton. Stay tuned!

Further Reading

Peter Mancall’s The Trials of Thomas Morton

Jack Dempsey’s annotated New English Canaan

1883 Reprint of Morton’s New English Canaan on Internet Archive, published by Charles Francis Adams Jr and the Prince Society